CHAPTER 2

LAYING THE GROUNDWORK WITH PEOPLE’S DATA

THE ABILITY TO

PRODUCE EVIDENCE

While National Land Coalitions have forged partnerships, advocated, protested, and developed policies to inspire change towards people-centred land governance, we have bolstered their efforts with data.

This triennium, by equipping our network to use and produce people’s data initiatives like LANDex and LandMark, we gave the communities we work with the ability to produce evidence for productive dialogues with government actors, and – thereby – a seat at the table.

Time and again, people’s organisations gathered, managed, and utilised people’s data on land rights, exposing structural inequalities, advocating for transparency, and building collective action.

reports used people’s data for accountability

Using data to defend the defenders

environmental defenders have been killed since 2012 according to Global Witness

"Despite my husband being murdered, it has only strengthened our unity, and has made us stronger in our claim to the land."

Maria Leony Denagiba’

For the land and environmental defenders in our network and beyond, the fight to defend their land and natural resources is not a choice they take lightly. It is in defence of their way of life, belief system, and future. The fight confronts deep-rooted patterns of injustice, defies large political and economic powers and is incredibly dangerous, often fatal. Very little puts people more at risk than defending their right to land. According to Global Witness, 2,106 land and environmental defenders have been killed since 2012.

In the Philippines – one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a land rights defender – Teresita Tarlac was nearly run over by a tractor sent by former landowners who had not succeeded in bribing or threatening her off her land. Her colleague, Maria Leony Denagiba’s husband, was killed by armed guards sent by former landowners.

Stories like Denagiba’s continue to motivate us: to find better and stronger ways to support those on the frontlines of securing land rights for their communities.

This is part of the ILC pledge, to do what we can to protect our members and their communities who are criminalised, intimidated and marginalised for advocating change.

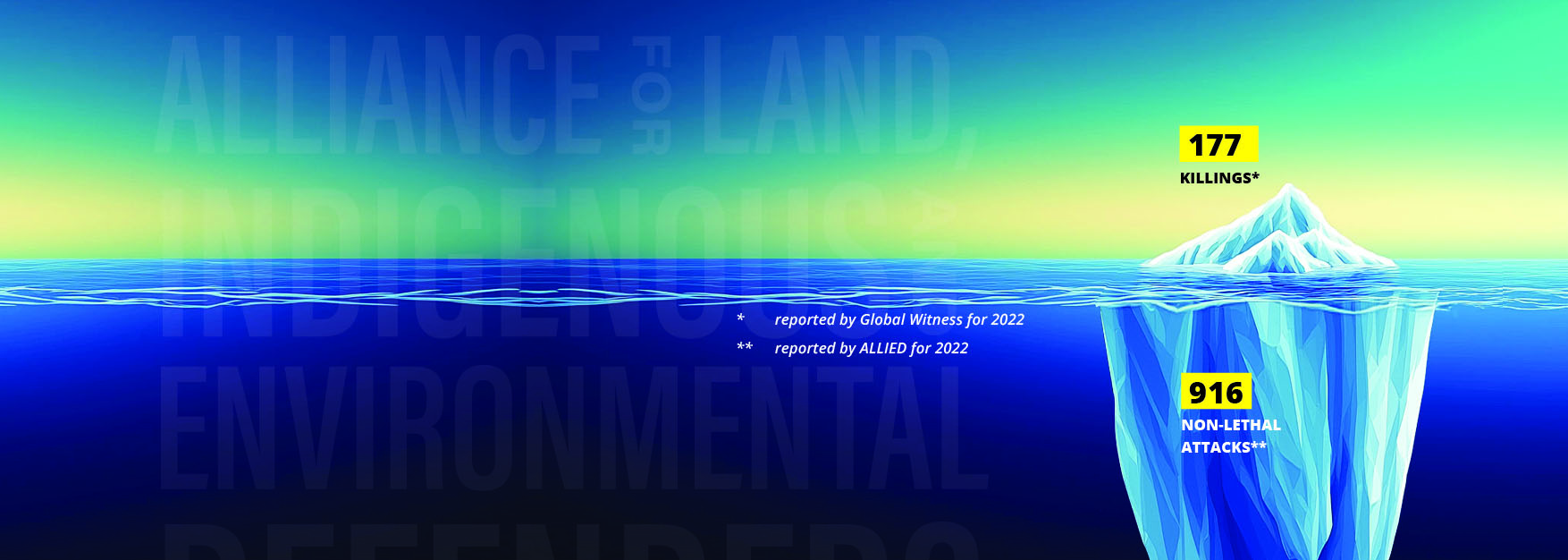

Uncovering the Hidden Iceberg

One of the most powerful tools we give our members to defend against such dangers is the transparency and visibility that people’s data provides. Between 2022 and 2024, as the climate crisis intensified and the green transition introduced new threats, our data confirmed what the stories we’ve told in this report already indicate. Defenders who protect critical biodiversity hotspots and carbon sinks are being increasingly targeted and criminalised. Moreover, for every killing of a defender documented in 2022, at least five non-lethal attacks took place.

This sinister trend is clearly outlined in our 2024 Hidden Iceberg report. The report – now in its third annual iteration – represents the first global effort to document non-lethal violence against Indigenous, land and environmental defenders. Year after year, it reveals that the killing of a defender is only the tip of a much deeper, hidden iceberg. In 2024, for the first time, we analysed a global data set covering 46 countries. Like in 2022 and 2023, we confirmed that Latin America (especially Colombia and Guatemala) – continues to be the most dangerous region for Indigenous, land and environmental defenders.

Hidden Iceberg underscored two more troubling trends in 2024. First, as in years past, Indigenous Peoples, like Reng Young Mro and his community in Bangladesh – are disproportionately targeted. Despite being an estimated six percent of the global population, they accounted for nearly one in every four attacks (24.2 percent). Second, across all countries, defenders speaking out against harms caused by large-scale mining and industrial agriculture – like Anci Tatawi in Indonesia or Teresita Tarlac in the Philippines – are consistently most at risk. These sectors were associated with 64.4% of attacks.

¨They offered me many millions [of pesos] to stop fighting for this land but I told myself if I give into the fear, the next generation will go hungry and I will be the only one who is rich. I was just not afraid. If they kill me, there will be more Teresitas to replace me and continue the fight.”

Teresita Tarlac

In 2024, we were also able to corroborate and track the extensive patterns of escalating violence that preceded the killing of defenders. We told, for example, the story of José Albeiro Camayo Guetio’s ascent up the iceberg – an Indigenous land rights defender from Colombia. Camayo Guietio, himself, was first threatened in 2014. He survived a series of escalating attacks in the following years, and – despite multiple requests for protection – was tragically murdered in 2022.

A Crucial Gap in state reporting

Our work on Hidden Iceberg is sobering. But we do not tell José’s story – or the stories of countless others like him – to revel in despair. Instead, by exposing the extensive patterns of violence that preceded the killing of Indigenous, land and environmental defenders, we are demanding accountability.

Without comprehensive, accurate, and timely data, governments cannot design effective protection mechanisms or public policies. They are failing in their responsibility to prevent and mitigate such violence and adhere to commitments they’ve made to the international community.

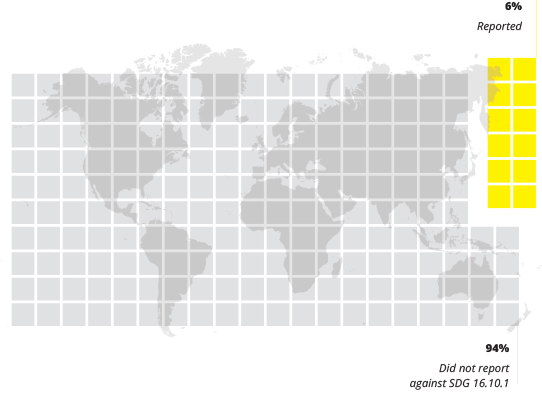

Each year, to call attention to their failures, we work with ALLIED on A Crucial Gap. This report reviews states’ obligations under SDG Indicator 16.10.1 to expose the limits of official reporting through their Voluntary National Reviews (VNRs).

A Crucial Gap is a rallying cry for urgent action. Governments have barely begun to acknowledge violence against human rights defenders. By 2023 – as reported by the 2024 report – only 7.7% of VNR countries reported any data for Indicator 16.10.1. In fact, of the 330 VNRs submitted since 2015, only 19 included data on attacks against human rights defenders at all. A Crucial Gap furthermore underscores that SDG Indicator 16.10.1 data lacks disaggregation by profession or affiliation, making it impossible to identify Indigenous, land, and environmental human rights defenders. This is despite evidence suggesting these groups represent half of all cases.

With six years remaining for governments to fulfil their commitments to the SDGs, Hidden Iceberg and A Crucial Gap are urgently vital advocacy tools. We will continue to use them to demand states track attacks against and protect human rights defenders, recognising the important role played by people-centred data.

Case study

New data reveals illegal logging is devastating Suriname’s forest

Step outside the Pengel International Airport in Paramaribo, Suriname and you are greeted with a large sign that reads, “Welcome to Suriname, the most forested country in the world.” The greeting, meant to be a beacon for adventurous tourists, is a point of contention to many.

Sitting below a faded picture of the country’s flora and fauna, the declaration is a particularly open affront to the Saamaka. The tribal people are descendants of African slaves who escaped and later negotiated their freedom with their Dutch colonizers. For centuries they have protected the country’s rich biodiversity and the 1.4 million hectares of their ancestral territory in the Amazon. They are a significant reason why 92% of Suriname’s forest cover is still intact. Despite this legacy, Suriname has failed to recognise and respect the territorial rights of the Saamaka.

Now, Saamaka people hope the LandMark platform will make a difference in a generations-long battle for their land and territorial rights. In 2024, LandMark released key updates. The mapping platform now covers 33.9% of the world’s land natural resources held and managed by Indigenous Peoples & local communities, bringing us much closer to the estimated 50 to 65% actually held. It also includes layers including biodiversity hotspots and mining and logging threats, allowing users to identify Indigenous Peoples and community lands with high-biodiversity value and identify industrial concessions and disturbances from mining, major dams and illegal logging.

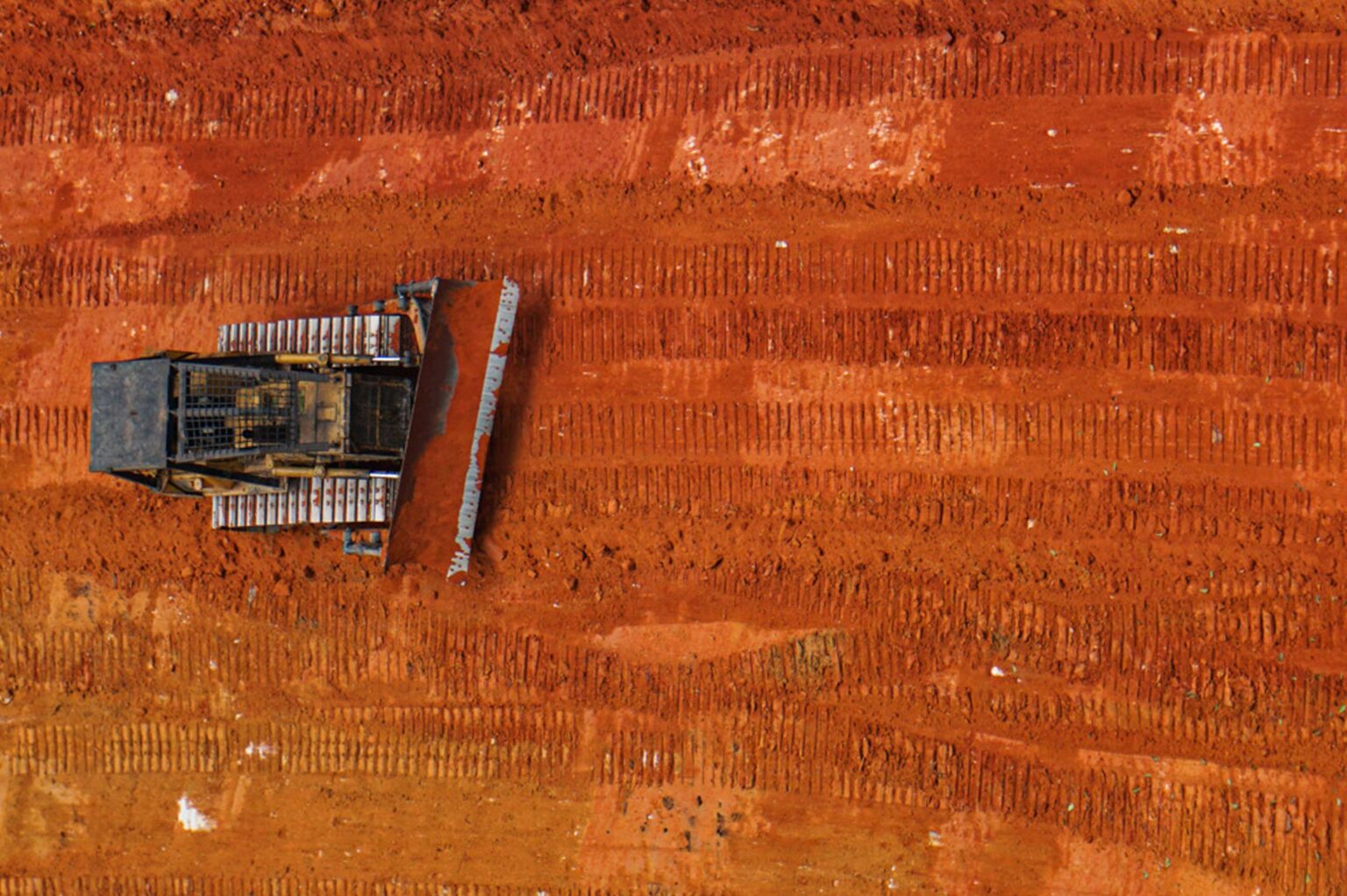

Such data is key for the Saamaka. In June 2024, an ILC study used LandMark data to uncover a staggering loss of biodiversity on their lands. Thanks to this data, the Saamaka proved that the Surinamese government has illegally granted 32% of Saamaka land—447,000 hectares—for logging and mining concessions, leading to the degradation of over 60,000 hectares, an area comparable to Singapore.

Further, it revealed that a striking 77% of all negative impacts to the Saamaka land have occurred since the 2007 ruling of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which mandated the government of Suriname stop the logging and mining, demarcate Saamaka territory, and legally recognise their collective rights. Most recently, a 2022 logging concession to Palmera N.V. – a multinational logging company –opened a new road in the forest despite the community’s opposition. The road has enabled access to hundreds of hectares of formerly pristine tropical rainforest. Spanning 56 kilometres at the end of 2023, by September 2024, Palmera N.V.’s road was 123 kilometres long.

The report’s findings have been used to strengthen legal cases to secure Saamaka land ownership and self-determination rights and were presented to the President’s Cabinet this past June with hopes of triggering action. But just months later, a follow-up study by the ILC proved that deforestation of Saamaka territory between June and September 2024 had increased by 57% compared to rates observed in the previous 6 years.

Together with members, partners – including World Resources Institute and Land Rights Now, the International Land Coalition is proud to have supported the Saamaka in their peaceful protest in June and a digital campaign during COP16 in October 2024, revitalising their change.org petition. In addition to garnering the attention of the international press, it reached more than 27,486 accounts and generated nearly 2,000 engagements across our digital channels.

We already know that such advocacy works. Our partnership with ALLIED on A Crucial Gap celebrated a huge victory in 2023 and 2024 when Kenya changed how the country reports on human rights defenders.

In 2023, ALLIED responded to a request from Kenya’s National Commission on Human Rights to submit data on attacks against Indigenous, land and environmental defenders. The following year, Kenya’s National Commission on Human Rights successfully validated the data and – under an official memorandum of understanding – forwarded it to the country’s National Statistics Office for integration into Kenya’s Voluntary National Review. Samson Omondi – who leads data work at the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights – emphasised the transformative power of people’s data in his work.

Kenya is a promising example of how people’s data can inspire state accountability – and, because of this, better public policies and more inclusive, pluralistic societies.

Case study

Data partnerships for progress

As the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights’ Samson Omondi told us, “Poorly collected, analysed, and disseminated data is worse than no data.” One of the ways we ensure maximum quality in the methods we use to collect, analyse, and disseminate data is through partnerships. Three stick out.

First, we work with ALLIED, a global network that tracks attacks on Indigenous, Land, and Environmental Defenders. The ALLIED Data Working Group, co-led by ILC, unites members in developing an integrated dataset to strengthen accountability and protection for such defenders. The partnership, producing impactful reports like Crucial Gap and Hidden Iceberg, has influenced key entities—from the UN to government agencies and human rights institutes—on improving defender protections. Significantly, it has also received endorsements from leading figures, such as Special Rapporteur Michel Forst, who has cited ALLIED’s data to call on governments to act. Following our Hidden Iceberg 2.0launch in New York in 2023, moreover, ILC was invited to present to the U.S. Department of State, guiding embassy responses to defender-related conflicts.

Second, in 2023, with the support of the European Union, Land Portal Foundation, Land Matrix Initiative, Prindex and ILC all came together. We joined forces to strengthen land data coordination in high-impact spaces to improve tenure security for land users and local communities through better-informed policies and programmes. The data partnershipemphasises collaboration, transparency, and minimising data fragmentation. It aligns with global frameworks like the SDGs and VGGTs and promotes FAIR and CARE principles to ensure land data is open, reusable, and supports better decision-making for equitable land rights and sustainable development.

Third, through LandMonitor, co-led by the International Land Coalition and the International Fund for Agricultural Development, we addressed a critical gap in national land tenure data and reporting in the Philippines. With an estimated outreach of 15,000 stakeholders across target groups and civil society organisations, LandMonitor’s people-centred work is substantial and far-reaching. The project gathered data from smallholders, indigenous communities and rural workers, drawing insights from LANDex, Prindex, LandMark and ALLIED. Our findings highlight significant disparities in women’s land rights and emphasise the need for decentralised institutions that empower community-level decision-making, particularly for women. The final report has shaped IFAD’s Country Strategy and a national investment, becoming a powerful advocacy tool for our members in discussions with State actors, including the Philippines Statistical Authority.

A second phase of the project is currently being carried out in Brazil. Preliminary results there highlight lack of official tenure data for key populations like Inidgenous Peoples, who face severe roadblocks in the full enjoyment of their established land rights. Members plan on using these findings as an advocacy tool to push for the establishment of a national land governance policy with an allocated budget, among other things.

Case study

Defending the defenders, an emergency fund

59 cases for land and environmental defenders, supporting 1,613 people across Latin America, Asia, and Africa between 2022 and 2024.

We stand behind our members on the frontlines of securing their communities’ land rights and commit to supporting them in the best ways possible.

One of the ways we do this is through an Emergency Fund, dedicated to supporting land and environmental defenders who face risks, criminalization, and marginalisation for protecting their communities’ land rights.

Between 2022 and 2024, emergency funds across Latin America, Asia, and Africa supported 59 cases for land and environmental defenders, supporting 1,613 people.

Advocating with people’s data

Hidden Iceberg and Crucial Gap are far from the only instruments we use to push authorities into acknowledging attacks against Indigenous, land and environmental defenders, breaches of their rights, or other challenges they face. In countries worldwide, our people’s data is gaining legitimacy as more state and international actors depend on it to – as Samson Omond put it – “fill in the gaps,” that states – limited by resources, funding or scope – cannot reach.

Just as such data strengthens broader advocacy efforts for land rights commitments, people’s organisations use it to build collective momentum towards their specific demands.

Women in Guatemala use data

to prove local reality

After Guatemala’s 2021 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) report failed to address key issues such as rural women’s unequal access to land and the criminalisation of women land defenders, Indigenous women’s organisations created a data-based counter-narrative.

In their 2023 alternative report, members used Prindex data to show that rural women are 5.5% less likely to possess land documentation and that Indigenous and Afro-descendant women who live on communal lands feel significantly less secure in their land rights than men. The report also underscored the significance of the rural gender income gap, with women earning 12.01% less than men for agricultural activities.

After finishing the report, our Women for Women Mentoring and Solidarity network – a key network of ILC women who uplift each other in their individual and collective struggles for gender justice – stepped in to help take it to the next level. With the network’s backing, Guatemalan land rights defenders presented the findings a the CEDAW forum in Geneva in 2023. There, they turned this data into a powerful advocacy tool, asking the government to commit to updating data on land tenure disaggregated by gender and to review land ownership criteria that currently discriminate against women who pursue higher education or choose not to have children.

Farmers in Togo shed light

on obstacles to land ownership

In Togo, the National Land Coalition – and farmer’s organisations within it – helped elaborate LANDex’s SDG Shadow Report.

The results underscored that despite being central to the country’s food security, only 12% of family farmers have received financial assistance, with women accounting for just 1.3% of that aid. In the report, farmers country-wide voiced a common issue: most lease their land with no path to ownership. Togo’s National Land Coalition coordinator, Abdou-Rachidou Matcheri emphasised the importance of this data to creating a clear pathway for land ownership and ensuring family farmers have access to the necessary financial and technical resources:

“This report is very important for us because we think that with it, the decision-makers can change something,” he told us. “Working with these different participants at the regional level has allowed us to understand concretely, what is happening with these small-scale and women farmers in our region.”

Abdou Rachidou Matcheri

Youth influence Colombia’s public policy

With ILC’s targeted support, rural youth in Colombia – the Young Entrepreneurs Association (ASOJE) – gathered and collected data that influenced the government’s public policy plans, demonstrating the potential of people’s data for democratic systems change. After ASOJE presented its findings to the government, Colombia incorporated them into the first draft of its public policy chapter on rural youth.

The same year, we renewed ILC’s commitment to youth, updating LANDex to align with youth land rights priorities. After extensive training and consultations with youth on land data, we created a Youth Data Package, which became an integral part of the new, inclusive indicators for LANDex 2.0.

Indigenous Peoples celebrate victory at COP16

Just as Colombian youth celebrated a data victory nationally, Indigenous Peoples and local communities celebrated a victory in 2024 during the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) COP16 in Cali, Colombia.

The work started in 2023 when ILC joined a technical working group on a land use and change indicator to advance the development and operationalisation of the Convention on Biodiversity’s Traditional Knowledge Indicator on Land Tenure and Use (HI 22.1). Together with the Food and Agricultural Organization, Prindex, LandMark, Indigenous Navigator, Forest Peoples Program, UN-Habitat and RRI (among others), ILC was instrumental in advocating for the indicator and developing methodologies to measure it.

At 2024’s CBD COP16 governments officially endorsed the indicator for headline status under Target 22. The indicator is a particularly important accountability mechanism, ensuring that Indigenous Peoples and local communities’ land rights are protected and that they are recognised as ecosystem guardians. Starting in 2026, countries will be required to report on the recognition of land rights for Indigenous Peoples and local communities in their national reports to the Convention on Biological Diversity.